Specimen Stories

Have you ever wondered what secrets lurk in the basement of a natural history museum? Museums around the world are the keepers of vast natural history collections with millions of specimens, ranging from fish in jars, to mammal skeletons and dinosaur fossils. The majority of these specimens are not on display, but form an invaluable resource to researchers. But what exactly can we learn from natural history collections? What stories do the specimens tell us? In this podcast, I talk to the scientists working in collections, and explore some of the amazing and surprising science they discovered.

Listen on Spotify, Apple podcasts or Google podcasts.

EPISODE 1 | SUPER-BLACK FEATHERS with DAKOTA McCOY

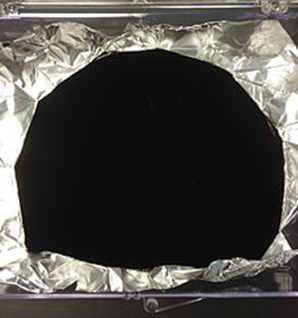

Super-black materials are blacker than black - they are so good at capturing light that almost no light escapes them. While a normal black object still reflects some light, which allows you to see the shape of the object, super-black objects appear almost shapeless. You can see this effect clearly in the image of Vantablack below, which is a human-made super-black material. But how do birds produce super-black colors? And why do they produce them? What can engineers learn from nature’s way of making super-black? To answer these questions, I talk to Dakota (Cody) McCoy, who discovered super-black bird plumage while being a student at Yale University. Cody is currently a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University, and she’s interested in how nature have come up with clever ways to modify light, and what we can learn from nature in developing new materials.

From left to right: Dr. Dakota McCoy; Vantablack material deposited on aluminium foil - the Vantablack in the middle is as wrinkled as the aluminium foil, yet this structure is invisible (image by Surrey NanoSystem, CC-BY-SA 3.0); a superb bird of paradise in display pose - showing both super-black plumage and iridescent blue feathers. If you doubt that this is really a picture of a bird, check out this excellent video explaining the shape-shifting magic of the superb bird of paradise (image by Tim Laman, CC-BY 4.0).

If you want to take a deeper dive into super-black plumage, check out Cody and collaborators’ papers on the topic:

Structural absorption by barbule microstructures of super black bird of paradise feathers

Convergent evolution of super black plumage near bright color in 15 bird families

Structurally assisted super black in colourful peacock spiders

EPISODE 2 | WEIRD AND WONDERFUL FISH with KORY EVANS

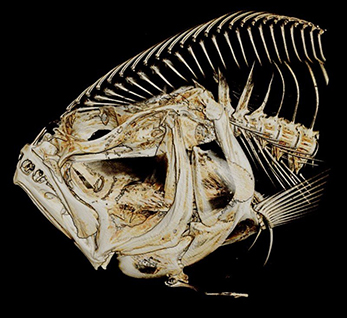

How do you evolve to have the entire right side of your face moving to the left side? Seems like a pretty outlandish thing to do - but the humble flatfish achieves just that feat during its lifespan. In this episode, I talk to Kory Evans, Assistant Professor at Rice University, to learn much more about how strange fish skulls evolve, and what this can tell us more broadly about how extraordinary lifeforms evolve. I promise, you will want to take a closer look at fish after this episode!

From left to right: Prof. Kory Evans at work in the ichthyology collections of the Bell Museum of Natural History; the asymmetric face of a flatfish (by Natural England/Tom Daguerre CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0); CT-scanned skull of a flatfish (by Kory Evans).

From left to right: Prof. Kory Evans at work in the ichthyology collections of the Bell Museum of Natural History; the asymmetric face of a flatfish (by Natural England/Tom Daguerre CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0); CT-scanned skull of a flatfish (by Kory Evans).

If you want to look at some of the diversity of fish skulls yourself, head over to the collection of fish CT scans at morphosource.org, part of an ambitious project to #ScanAllFishes.

Learn more about the evolution of flatfish in Kory and colleagues’ paper:

Integration drives rapid phenotypic evolution in flatfishes

EPISODE 3 | FORAMINIFERA - TINY TIME MACHINES OF THE OCEAN with MARINA RILLO

How do we know what the climate was like thousands or even millions of years ago? We would need some kind of record of what the planet was like in the past. Ideally, we’d want a record with not only high temporal resolution - showing the changes year by year - but also with wide geographical scope, showing changes not only in one place, but globally. It turns out that an obscure microscopic sea organism can provide just that for us - foraminiferans. In this episode, I talk to Marina Rillo, who is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oldenburg in Germany. Marina use modern and historical collections of foraminifera to study how ecosystems in the oceans have changed through time, and what we can learn from this in predicting future changes.

From left to right: Dr. Marina Rillo on the marine expedition FORAMFLUX; microscope image of foraminiferan shells (by Marina Rillo); sediment samples from the Henry Buckley Collection at the London NHM; evidence of the drama behind sediment collections - a news story on the rescue of scientists stranded in the ice, and the sediment samples they managed to take with them.

If you want to learn more about the Buckley Collection, check out this blog post from the NHM. To see the beauty of forams yourself, browse the digitized foram collection Marina created, or check out the foram library she helped create with a team at Yale.

The papers we discuss in the podcast can be found here:

Surface Sediment Samples From Early Age of Seafloor Exploration Can Provide a Late 19th Century Baseline of the Marine Environment

Endless Forams: >34,000 Modern Planktonic Foraminiferal Images for Taxonomic Training and Automated Species Recognition Using Convolutional Neural Networks

Intraspecific size variation in planktonic foraminifera cannot be consistently predicted by the environment

EPISODE 4 | FLUTTERING MIGRATIONS with MICAH FREEDMAN

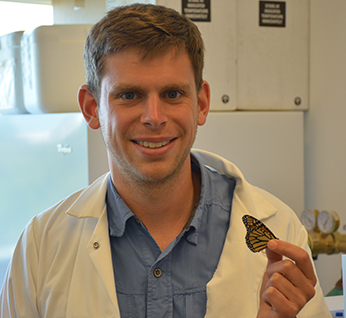

Fall is upon us and it is high time for many animals to be on the move. Millions of birds migrate south each fall. But another animal currently migrating is the monarch butterfly. The monarch butterflies migrate over 2000 kilometers every fall to reach their wintering grounds in Mexico. It’s an astonishing journey for an insect. But not all monarchs migrate. Some populations stay cosy and warm year round on tropical islands in the Pacific ocean. How did these monarchs end up there? And how did they loose their ability to migrate? Micah Freedman, who is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Chicago, realized that museum collections of monarchs could give us unique insights into these questions. In this episode, I talk to Micah about his research on monarchs, why they migrate, and how and why some monarchs lost migration altogether.

From left to right: Dr. Micah Freedman holding a monarch; monarch butterfly in Guam feeding on a tropical milkweed species (by Micah Freedman); a monarch specimen held at the London Natural History Museum (by NHM, CC0-1.0). Monarchs sometimes get blown over to the UK by storms - but don’t survive as there is no milkweed for them to eat.

To learn more about Micah’s research, check out the papers we discussed in the podcast:

Two centuries of monarch butterfly collections reveal contrasting effects of range expansion and migration loss on wing traits

Wing morphology in migratory North American monarchs: characterizing sources of variation and understanding changes through time

Non-migratory monarch butterflies, Danaus plexippus (L.), retain developmental plasticity and a navigational mechanism associated with migration

Are eastern and western monarch butterflies distinct populations? A review of evidence for ecological, phenotypic, and genetic differentiation and implications for conservation

You can follow the monarchs migration live on a map built by the organisation Journey North, which is based on citizen scientist reports of monarchs. If you happen to live where there are monarchs, you can also report your own sightings here! A similar program for monarchs on the West Coast is Western Monarch Milkweed Mapper.

Another way to get involved in monarch research is through the program MonarchWatch, which tags hundreds of monarchs each year to learn about their movements. This is also an excellent source of information on monarchs.

EPISODE 5 | A FROG’S EYE VIEW OF THE WORLD - with KATE THOMAS

There is a saying that someone is “eagle-eyed” if they spot minute details - and if I asked you to name an animal with good eyesight, you’d probably think of an owl or an eagle. But in this episode we’ll hear that the largest relative eye size of any vertebrate is found in an entirely different group of animals - frogs and toads. Kate Thomas, who is a postdoctoral researcher at the Natural History Museum in London, surveyed eye size in hundreds of frogs and toads and asked how eye size has evolved in this diverse group. Why do frogs and toads have such large eyes? How does eye size affect vision in the first place? And did you know that many frogs can see colors in the dark?

From left to right: Dr. Kate Thomas with a frog friend; the Natural History Museum in London, where Katie collected data on frog specimens; a frog specimen from the 1800s - just one of many hundreds kept in the herpetology collections at NHM; a colourful tree frog exemplifying how many frogs have relatively large eyes compared to their body size.

Check out two of Katie’s favourite frogs - the mighty rain frog (left), and the fierce Budgett’s frog (right) .

The paper we discuss in the podcast can be found here:

Eye size and investment in frogs and toads correlate with adult habitat, activity pattern and breeding ecology

…and if you’re more curious about frog vision - check out some of the other cool papers by Katie and collaborators that we didn’t have time to talk about in the podcast:

Diversity and evolution of amphibian pupil shapes

Eye‐body allometry across biphasic ontogeny in anuran amphibians

Genomic and Spectral Visual Adaptation in Southern Leopard Frogs during the Ontogenetic Transition from Aquatic to Terrestrial Light Environments